Opportunistic Systemic Mycoses

These are fungal infections of the body which occur almost exclusively in debilitated patients whose normal defence mechanisms are impaired.

The organisms involved are cosmopolitan fungi which have a very low inherent virulence. The increased incidence of these infections and the diversity of fungi causing them, has parallelled the emergence of AIDS, more aggressive cancer and post-transplantation chemotherapy and the use of antibiotics, cytotoxins, immunosuppressives, corticosteroids and other macro disruptive procedures that result in lowered resistance of the host.

| Disease | Causative organisms | Incidence |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillosis | Aspergillus fumigatus complex, A. flavus, complex, A. terreus complex etc. |

Common |

| Candidiasis | Candida, Debaryomyces, Kluyveromyces, Meyerozyma, Pichia, etc. |

Common |

| Cryptococcosis | Cryptococcus spp. especially C. neoformans and C. gattii. |

Uncommon |

| Hyalohyphomycosis | Penicillium, Paecilomyces, Beauveria, Fusarium, Scopulariopsis etc. |

Rare |

| Phaeohyphomycosis | Cladophialophora, Exophiala, Bipolaris, Exserohilum etc. |

Uncommon |

| Scedosporiosis (Pseudallescheriasis) |

Scedosporium and Lomentospora. | Rare |

| Zygomycosis (Mucormycosis) |

Rhizopus, Mucor, Rhizomucor, Lichtheimia etc. |

Rare |

Mycoses descriptions

-

Aspergillosis

Aspergillosis is a spectrum of diseases of humans and animals caused by members of the genus Aspergillus. These include (1) mycotoxicosis due to ingestion of contaminated foods; (2) allergy and sequelae to the presence of conidia or transient growth of the organism in body orifices; (3) colonisation without extension in preformed cavities and debilitated tissues; (4) invasive, inflammatory, granulomatous, narcotising disease of lungs, and other organs; and rarely (5) systemic and fatal disseminated disease. The type of disease and severity depends upon the physiologic state of the host and the species of Aspergillus involved. The etiological agents are cosmopolitan and include Aspergillus fumigatus complex, A. flavus complex, A. niger complex, A. nidulans and A. terreus complex.

Clinical manifestations:

Pulmonary aspergillosis: including allergic, aspergilloma and invasive aspergillosis.

The clinical manifestations of pulmonary aspergillosis are many, ranging from harmless saprophytic colonisation to acute invasive disease.Allergic aspergillosis is a continuum of clinical entities ranging from extrinsic asthma to extrinsic allergic alveolitis to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis) caused by the inhalation of Aspergillus conidia. Features include asthma, intermittent or persistent pulmonary infiltrates, peripheral eosinophilia, positive skin test to Aspergillus antigenic extracts, positive immunodiffusion precipitin tests for antibody to Aspergillus, elevated total IgE, and elevated specific IgE against Aspergillus. Plug expectoration and a history of chronic bronchitis are also common. Symptoms may be mild and without sequelae, but recurrent episodes frequently progress to bronchiectasis and fibrosis.

Non-invasive aspergillosis or aspergilloma (fungus ball), is caused by the saprophytic colonisation of pre-formed cavities, usually secondary to tuberculosis or sarcoidosis. Features often include hemoptysis with blood stained sputum, positive immunodiffusion precipitin tests for antibody to Aspergillus, and elevated specific IgE against Aspergillus. However, many cases are asymptomatic and are usually found by routine chest x-ray.

Aspergilloma formed by the colonisation of a pre-formed lung cavity.

Acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Predisposing factors include prolonged neutropenia, especially in leukemia patients or in bone marrow transplant recipients, corticosteroid therapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy and to a lesser extent patients with AIDS or chronic granulomatous disease. Clinical symptoms may mimic acute bacterial pneumonia and include fever, cough, pleuritic pain, with hemorrhagic infarction or a narcotising bronchopneumonia. The typical patient is granulocytopenic and receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics for unexplained fever. Radiological features may be non-specific and tests for serum antibody precipitins are also usually negative. Clinical recognition is essential as this is the most common form of aspergillosis in the immunosuppressed patient.

Chronic narcotising aspergillosis is an indolent, slowly progressive, "semi-invasive" form of infection seen in mildly immunosuppressed patients, especially those with a previous history of lung disease. Diabetes mellitus, sarcoidosis and treatment with low-dose glucocorticoids may be other predisposing factors. Common symptoms include fever, cough and sputum production; positive serum antibody precipitins may also be detected.

Disseminated aspergillosis:

Hematogenous dissemination to other visceral organs may occur, especially in patients with severe immunosuppression or intravenous drug addiction. Abscesses may occur in the brain (cerebral aspergillosis), kidney (renal aspergillosis), heart, (endocarditis, myocarditis), bone (osteomyelitis), and gastrointestinal tract. Ocular lesions (mycotic keratitis, endophthalmitis and orbital aspergilloma) may also occur, either as a result of dissemination or following local trauma or surgery.Aspergillosis of the paranasal sinuses:

Two types of paranasal sinus aspergillosis are generally recognised. (1) A non-invasive "aspergilloma" form, primarily seen in non-immunosuppressed individuals. Predisposing factors include a history of chronic sinusitis and poorly draining sinuses with excessive mucus. (2) An invasive form, usually seen in the immunosuppressed patient. This form has a similar clinical setting to that seen in rhinocerebral zygomycosis; and symptoms include fever, rhinitis and signs of invasion into the orbit.Cutaneous aspergillosis:

Cutaneous aspergillosis is a rare manifestation that is usually a result of dissemination from primary pulmonary infection in the immunosuppressed patient. However, cases of primary cutaneous aspergillosis also occur, usually as a result of trauma or colonisation. Lesions manifest as erythematous papules or macules with progressive central necrosis.Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Sputum, bronchial washings and tracheal aspirates from patients with pulmonary disease and tissue biopsies from patients with disseminated disease.Direct microscopy:

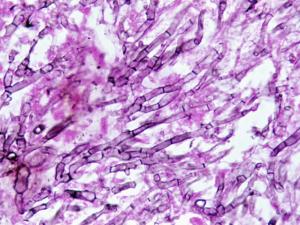

(a) Sputum, washings and aspirates make wet mounts in either 10% KOH & Parker ink or Calcofluor and/or Gram stained smears; (b) Tissue sections should be stained with H&E, GMS and PAS digest. Note Aspergillus hyphae may be missed in H&E stained sections. Examine specimens for dichotomously branched, septate hyphae.Click images below to expand:

Interpretation:

The presence of hyaline, branching septate hyphae, consistent with Aspergillus in any specimen, from a patient with supporting clinical symptoms should be considered significant. Biopsy and evidence of tissue invasion is of particular importance. Remember direct microscopy or histopathology does not offer a specific identification of the causative agent.Culture:

Clinical specimens should be inoculated onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar. Colonies are fast growing and may be white, yellow, yellow-brown, brown to black or green in colour.

A. fumigatus growing in air sacs of a hen during epidemic aspergillosis in poultry.

Interpretation:

Aspergillus species are well recognised as common environmental airborne contaminants, therefore a positive culture from a non-sterile specimen, such as sputum, is not proof of infection. However, the detection of Aspergillus (especially A. fumigatus and A. flavus) in sputum cultures, from patients with appropriate predisposing conditions, is likely to be of diagnostic importance and empiric antifungal therapy should be considered. Unfortunately, patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, often have negative sputum cultures making a lung biopsy a prerequisite for a definitive diagnosis.Serology:

Immunodiffusion tests for the detection of antibodies to Aspergillus species have proven to be of value in the diagnosis of allergic, aspergilloma, and invasive aspergillosis. However, they should never be used alone, and must be correlated with other clinical and diagnostic data. Several antigen tests for the detection of Aspergillusfrom blood, urine and CFS are now available. The (1→3)- β-D- glucan test detects a wide variety of fungal pathogens including Aspergillus, Candida, Fusarium, Trichosporon and several commercial kits (FungiTec G, Fungitell) are available.

Platelia Aspergillus ELISA galactomannan test.

However the most widely used system is the Aspergillusgalactomannan ELISA test (Platelia® Aspergillus ELISA kit). The Aspergillus galactomannan (GM) test has a reported specificity of 89-93%; sensitivity of 61-71%; NPV of 95-98%; PPV of 26-53% (Meta-analysis 27 studies Pfeiffer et al. CID 2006). However as galactomannan is rapidly eliminated from blood - serial screening twice weekly for optimal diagnosis is recommended.

Identification:

Aspergillus colonies are usually fast growing, white, yellow, yellow-brown, brown to black or shades of green, and they mostly consist of a dense felt of erect conidiophores. Conidiophores terminate in a vesicle covered with either a single palisade-like layer of phialides (uniseriate) or a layer of subtending cells (metulae) which bear small whorls of phialides (the so-called biseriate structure). The vesicle, phialides, metulae (if present) and conidia form the conidial head. Conidia are one-celled, smooth- or rough-walled, hyaline or pigmented and are basocatenate, forming long dry chains which may be divergent (radiate) or aggregated in compact columns (columnar). Some species may produce Hülle cells or sclerotia.Causative agents:

Aspergillus spp. Aspergillus flavus complex, Aspergillus fumigatus complex, Aspergillus nidulans complex, Aspergillus niger complex, Aspergillus terreux complex.Further reading:

Chandler FW., W. Kaplan and L. Ajello. 1980. A colour atlas and textbook of the histopathology of mycotic diseases. Wolfe Medical Publications Ltd. London.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co.

Warnock DW and MD Richardson. 1991. Fungal infection in the compromised patient. 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons. -

Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a primary or secondary mycotic infection caused by members of the genus Candida and other related genera. The clinical manifestations may be acute, subacute or chronic to episodic. Involvement may be localized to the mouth, throat, skin, scalp, vagina, fingers, nails, bronchi, lungs, or the gastrointestinal tract, or become systemic as in septicemia, endocarditis and meningitis. In healthy individuals, Candida infections are usually due to impaired epithelial barrier functions and occur in all age groups, but are most common in the newborn and the elderly. They usually remain superficial and respond readily to treatment. Systemic candidiasis is usually seen in patients with cell-mediated immune deficiency, and those receiving aggressive cancer treatment, immunosuppression, or transplantation therapy.

-

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis is a chronic, subacute to acute pulmonary, systemic or meningitic disease, initiated by the inhalation of infectious propagules (basidiospores and/or desiccated yeast cells) from the environment. Primary pulmonary infections have no diagnostic symptoms and are usually subclinical. On dissemination, the fungus usually shows a predilection for the central nervous system, however skin, bones and other visceral organs may also become involved.

Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii are the principle pathogenic species. Naganishia albida (formerly Cryptococcus albidus) and Patiliotrema laurentii (formely Cryptococcus laurentii) have on occasion also been implicated in human infection.

Clinical manifestations:

Cryptococcus is an encapsulated basidiomycete yeast-like fungus with a predilection for the respiratory and nervous system of humans and animals. Two species, C. neoformans and C. gattii are distinguishable biochemically and by molecular techniques.

In humans, C. neoformans affects immunocompromised hosts predominantly and is the commonest cause of fungal meningitis; worldwide, 7-10% of patients with AIDS are affected. AIDS associated cryptococcosis accounts for 50% of all cryptococcal infections reported annually and usually occurs in HIV patients when their CD4 lymphocyte count is below 200/mm3. Meningitis is the predominant clinical presentation with fever and headache as the most common symptoms. Secondary cutaneous infections occur in up to 15% of patients with disseminated cryptococcosis and often indicate a poor prognosis. Lesions usually begin as small papules that subsequently ulcerate, but may also present as abscesses, erythematous nodules, or cellulitis. This variety is found worldwide.

In contrast, the distribution of cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus gattii is geographically restricted, non-immunocompromised hosts are usually affected, large mass lesions in lung and/or brain (cryptococcomas) are characteristic and morbidity from neurological disease is high. Human disease is endemic in Australia, Papua New Guinea, parts of Africa, the Mediterranean region, India, south-east Asia, Mexico, Brazil, Paraguay and Southern California.

Pulmonary cryptococcosis:

Asymptomatic carriage of Cryptococcus has been reported from the respiratory tract, especially sputum and from skin in healthy people as a result of normal environmental exposure. In addition, patients with chronic lung disease, such as bronchitis and bronchiectasis, may also have asymptomatic colonization, with Cryptococcus being isolated from their sputum over many years.Subclinical cryptococcosis may result of environmental exposure, normal individuals may experience a self-limiting pneumonia with accompanying sensitization. Most primary infections of this type have no diagnostic symptoms and are usually discovered only by routine chest x-ray. When present, symptoms include cough, low-grade fever and pleuritic pain.

X-ray showing pulmonary cryptococcal infection [right upper lobe].

Invasive pulmonary cryptococcosis may occur in some patients when primary infections may not readily resolve in some patients, leading to a more chronic pneumonia progressing slowly over several years. Patients may become pyrexic and have an accompanying cough, however many pulmonary lesions are often asymptomatic, especially when chronic granulomas are formed. Chronic pulmonary cryptococcosis also increases the risk of dissemination to the central nervous system.

Central nervous system:

Dissemination to the brain and meninges is the most common clinical manifestation of cryptococcosis and includes meningitis, meningoencephalitis or expanding cryptococcoma.Meningitis is the most common clinical form, accounting for up to 85% of the total number of cases, however the clinical signs are rarely dramatic. Symptoms usually develop slowly over several months, and initially include headache, followed by drowsiness, dizziness, irritability, confusion, nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness and focal neurological defects, such as ataxia. Diminishing visual acuity and coma may also occur in later stages of the infection. Acute onset cases may also occur, especially in patients with widespread disease, and these patients may deteriorate rapidly and die in a matter of weeks.

Meningoencephalitis due to invasion of the cerebral cortex, brain stem and cerebellum is an uncommon, rapid fulminate infection, often leading to coma and death within a short time. Symptoms include slow response to treatment and signs of cerebral edema or hydrocephalitis, especially papilledema.

MRI scan showing multiple cryptococcomas [white masses] in the brain.

Cutaneous cryptococcosis:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in the form of ulcerated lesions or cellulitis occasionally occurs, especially in immunosuppressed patients. These lesions may resolve spontaneously or with systemic antifungal treatment. However, all patients with skin lesions should be monitored carefully for possible dissemination to the central nervous system.Secondary cutaneous infections occur in up to 15% of patients with disseminated cryptococcosis and often indicate a poor prognosis. Lesions usually begin as small papules that subsequently ulcerate, but may also present as abscesses, erythematous nodules, or cellulitis.

In patients with AIDS, skin manifestations represent the second most common site of disseminated cryptococcosis. Lesions often occur on the head and neck and may present as papules, nodules, plaques, ulcers, abscesses, cutaneous ulcerated plaques, herpetiform lesions, lesions simulating both molluscum contagiosum and Kaposi's sarcoma. Anal ulceration may also occur.

Click images below to expand:

Cryptococcosis of bone:

Osseous cryptococcosis occurs in up to 10% of disseminated cases and may involve bony prominences, cranial bones and vertebrae. The lesions are lytic without periosteal reaction and symptoms of dull pain on movement are reported. Occasional cases of arthritis have also been reported, mostly involving the knee joint.Ocular cryptococcosis:

Ocular manifestations of cryptococcosis most commonly include papilledema and optic atrophy, due to raised intracranial pressure. Other ocular signs of cryptococcosis are uncommon and usually occur as a result of dissemination.Other forms of cryptococcosis:

Cryptococcus neoformans is often isolated from urine of patients with disseminated infection. Occasionally, signs of pyelonephritis or prostatitis may be observed. Other rare forms of cryptococcosis include adrenal cortical lesions, endocarditis, hepatitis, sinusitis, and localized oesophageal lesions.Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), biopsy tissue, sputum, bronchial washings, pus, blood and urine.Direct microscopy:

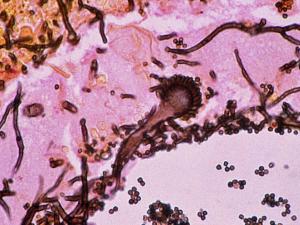

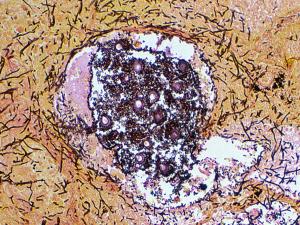

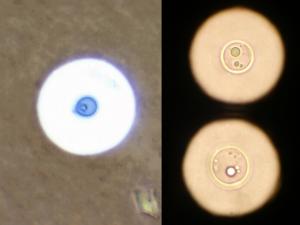

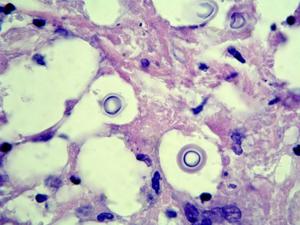

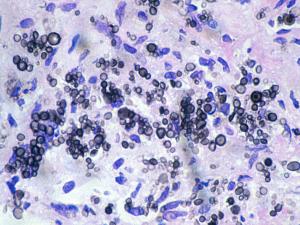

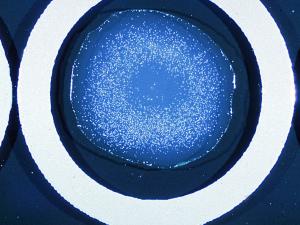

(a) For exudates and body fluids make a thin wet film under a coverslip using India ink to demonstrate encapsulated yeast cells. Sputum and pus may need to be digested with 10% KOH prior to India ink staining. (b) For tissue sections use PAS digest, GMS and H&E, mucicarmine stain is also useful to demonstrate the polysaccharide capsule. Examine for globose to ovoid, budding yeast cells surrounded by wide gelatinous capsules. Note, non-encapsulated variants, although rare, may also occur.Interpretation:

The demonstration of encapsulated yeast cells in CSF, biopsy tissue, blood or urine should be considered significant, even in the absence of clinical symptoms. Positive sputum specimens should be considered potentially significant, even though Cryptococcus may also occur in respiratory secretions as a saprophyte. Basically, all patients with a positive microscopy for cryptococci, from any site should be investigated for disseminated disease, especially by culture and antigen detection.Click images below to expand:

Culture:

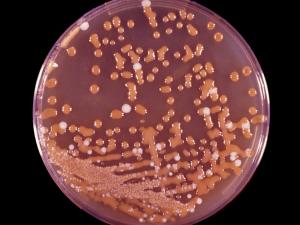

Inoculate specimens onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar. Look for translucent, smooth gelatinous colonies, later becoming very mucoid and cream in color.Interpretation:

The isolation of C. neoformans or C. gattii from any site should be considered significant and patients without clinical symptoms should be thoroughly investigated for disseminated disease. Positive culture of CSF is definitive. However, positive culture of respiratory secretions, especially in patients without clinical symptoms, needs to be interpreted with some caution, until additional supporting evidence is available. Isolation of Naganishia albida (Cryptococcus albidus) or Papiliotrema laurentii (Cryptococcus laurentii), should also be interpreted with caution as these species are infrequent pathogens and once again, additional supporting clinical and microscopic evidence is necessary.Click images below to expand:

Interpretation:

The isolation of C. neoformans or C. gattii from any site should be considered significant and patients without clinical symptoms should be thoroughly investigated for disseminated disease. Positive culture of CSF is definitive. However, positive culture of respiratory secretions, especially in patients without clinical symptoms, needs to be interpreted with some caution, until additional supporting evidence is available. Isolation of Naganishia albida (Cryptococcus albidus) or Papiliotrema laurentii (Cryptococcus laurentii), should also be interpreted with caution as these species are infrequent pathogens and once again, additional supporting clinical and microscopic evidence is necessary.Serology:

It should be noted that the detection of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide antigen in spinal fluid is now the method of choice for diagnosing patients with cryptococcal meningitis. In AIDS patients, cryptococcal antigen can be detected in the serum in nearly 100% of cases. However, in non-AIDS patients antigen detection in serum is less sensitive with only about 60% of patients with cryptococcosis reported as being positive. Note, serum specimens should be pretreated with pronase to enhance detection of antigen and avoid false negative results.Identification:

The genus Cryptococcus is characterized by globose to elongate yeast-like cells or blastoconidia that reproduce by multilateral budding. Pseudohyphae are absent or rudimentary. On solid media the cultures are generally mucoid or slimy in appearance. Red, orange or yellow carotenoid pigments may be produced, but young colonies of most species are usually non-pigmented, and are cream in color. Most strains have encapsulated cells with the extent of capsule formation depending on the medium. Under certain conditions of growth the capsule may contain starch-like compounds which are released into the medium by many strains. Within the genus Cryptococcus, fermentation of sugars is negative, assimilation of nitrate is variable and assimilation of inositol is positive. The genus Cryptococcus is similar to the genus Rhodotorula. The distinctive difference between the two is the assimilation of inositol, which is positive in Cryptococcus.Causative agents:

Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii.

Further reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Ellis, D.H. and T.J. Pfeiffer. 1992. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8:3

Ellis, D.H., D, Marriott and T. Sorrell. Candidial and Cryptococcal infections. An interactive CD-ROM , Pfizer Australia.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co.

Warnock DW and MD Richardson. 1991. Fungal infection in the compromised patient. 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons. -

Hyalohyphomycosis

A mycotic infection of man or animals caused by a number of hyaline (non-dematiaceous) hyphomycetes where the tissue morphology of the causative organism is mycelial. This separates it from phaeohyphomycosis where the causative agents are brown-pigmented fungi. Hyalohyphomycosis is a general term used to group together infections caused by unusual hyaline fungal pathogens that are not agents of otherwise-named infections; such as Aspergillosis. Etiological agents include species of Penicillium, Paecilomyces, Acremonium, Beauveria, Fusarium and Scopulariopsis.

Clinical manifestations:

The clinical manifestations of hyalohyphomycosis are many ranging from harmless saprophytic colonization to acute invasive disease. Predisposing factors include prolonged neutropenia, especially in leukemia patients or in bone marrow transplant recipients, corticosteroid therapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy and to a lesser extent patients with AIDS. The typical patient is granulocytopenic and receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics for unexplained fever.

Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Skin and nail scrapings; urine, sputum and bronchial washings; cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid and blood; tissue biopsies from various visceral organs and indwelling catheter tips.Direct microscopy:

(a) Skin and nail scrapings, sputum, washings and aspirates should be examined using 10% KOH and Parker ink or calcofluor white mounts; (b) Exudates and body fluids should be centrifuged and the sediment examined using either 10% KOH and Parker ink or calcofluor white mounts, (c) Tissue sections should be stained using PAS digest, Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS) or Gram stains. Note hyphal elements are often difficult to detect in H&E stained sections.Interpretation: The presence of hyaline, branching septate hyphae, similar to Aspergillus in any specimen, from a patient with supporting clinical symptoms should be considered significant. Biopsy and evidence of tissue invasion is of particular importance. Remember direct microscopy or histopathology does not offer a specific identification of the causative agent.

Culture of Chrysosporium [left] and Fusarium [right] showing typical colony colour for a hyaline hyphomycete ie any colour except brown, olivaceous black or black.

Culture:

Clinical specimens should be inoculated onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar.Interpretation:

The hyaline hyphomycetes involved are well recognized as common environmental airborne contaminants, therefore a positive culture from a non-sterile specimen, such as sputum or skin, needs to be supported by direct microscopic evidence in order to be considered significant. A supporting clinical history in patients with appropriate predisposing conditions, is also helpful. Culture identification is the only reliable means of distinguishing these fungi.Serology:

There are currently no commercially available serological procedures for the diagnosis of any of the infections classified under the term hyalohyphomycosis.Identification:

Culture characteristics and microscopic morphology are important, especially conidial morphology, the arrangement of conidia on the conidiogenous cell and the morphology of the conidiogenous cell.Causative agents:

Acremonium sp., Beauveria sp., Fusarium sp., Paecilomyces sp., Penicillium sp., Scopulariopsis sp. etc.Further reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Booth, C. 1977. Fusarium: laboratory guide to the identification of the major species. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, Surrey, England.

Burgess, L.W., and C.M. Liddell. 1983. Laboratory manual for Fusarium research. Fusarium Research Laboratory, Department of Plant Pathology and Agricultural Entomology. The University of Sydney, Australia.

Domsch, Gams and Anderson. 1980. Compendium of soil fungi Volume 1. Academic Press.

Hoog de GS and J Guarro. 1994. Atlas of Clinical Fungi from Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands. CBS publications may be ordered from Tinke van den-Berg-Visser, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, PO Box 273, 3740 AG Baarn, The Netherlands FAX + 31 2154 16142.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Warnock DW and MD Richardson. 1991. Fungal infection in the compromised patient. 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons. -

Phaeohyphomycosis

A mycotic infection of humans and lower animals caused by a number of dematiaceous (brown-pigmented) fungi where the tissue morphology of the causative organism is mycelial. This separates it from other clinical types of disease involving brown-pigmented fungi where the tissue morphology of the organism is a grain (mycotic mycetoma) or sclerotic body (chromoblastomycosis). The etiological agents include various dematiaceous hyphomycetes especially species of Exophiala, Phialophora, Bipolaris, Exserohilum, Cladophialophora, Verruconis, Aureobasidium, Cladosporium, Curvularia and Alternaria. Ajello (1986) listed 71 species from 39 genera as causative agents of phaeohyphomycosis.

-

Scedosporiosis (Pseudallescheriasis)

Scedosporium and Lomentospora infection

A spectrum of disease similar in terms of variety and severity to those caused by Aspergillus. The vast majority of infections are mycetomas, the remainder include infections of the eye, ear, central nervous system, internal organs and more commonly the lungs. Infections result from either inhalation of air-borne conidia or by the traumatic implantation of fungal elements due to a penetrating injury. The etiological agents are Scedosporium apiospermum,Scedosporium aurantiacum, Scedosporium boydii and Lomentospora prolificans.

Clinical manifestations:

Scedosporium apiospermum, Scedosporium boydii and Scedosporium aurantiacum infections:

Non-invasive colonization of the external ear and pulmonary colonization in patients with poorly draining bronchi or paranasal sinuses and "fungus ball" formation in pre-formed cavities are similar to those seen in Aspergillus.

Invasive infections in normal patients are usually caused by traumatic implantation. Mycetoma, where the fungus exists in tissue as resistant microcolonies or grains is the most common infection in the normal patient. This is followed by penetrating joint injuries, especially to the knee, resulting in arthritis and osteomyelitis. Other manifestations include mycotic keratitis and non-mycetoma like cutaneous and subcutaneous infections.

Invasive infections have also been reported in patients receiving treatment with corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation, leukemia, lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematous or Crohn's disease. Infections include invasive sinusitis, pneumonia, arthritis with osteomyelitis, cutaneous and subcutaneous granulomata, meningitis, brain abscesses, endophthalmitis, and disseminated systemic disease.

Lomentospora prolificans infections:

The spectrum of clinical manifestations are similar to that described above for Scedosporium. Disseminated disease has been reported in immunosuppressed patients especially those with prolonged neutropenia and post-transplantation therapy. Colonization of the external ear, paranasal sinuses and lung, including "fungus ball" have been reported. Cases of onychomycosis and mycotic keratitis have also been documented. However, localized invasive infections, especially septic arthritis and osteomyelitis following penetrating injuries to joints, are now an emerging clinical problem, accounting for 80% of the reported cases. Culture identification is important, because this fungus is often resistant to antifungal therapy and treatment may require surgical intervention.

Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Sputum, bronchial washings and tracheal aspirates from patients with pulmonary disease and tissue biopsies from patients with subcutaneous and disseminated disease.Direct microscopy:

(a) Sputum, washings and aspirates make wet mounts in either 10% KOH & Parker ink or Calcofluor and/or Gram stained smears; (b) Tissue sections should be stained with H&E, GMS and PAS digest. Note hyphal elements of Scedosporium species and Lomentospora prolificans are indistinguishable from those of Aspergillus hyphae and may be missed in H&E stained sections. Examine specimens for branched, septate hyphae.Interpretation:

The presence of branching septate hyphae in any specimen, from a patient with supporting clinical symptoms should be considered significant. Biopsy and evidence of tissue invasion is of particular importance. Remember culture is necessary for a specific identification of the causative agent.Culture:

Colonies are fast growing and are greyish-white, to olive-grey to black with a suede-like to downy surface texture.Interpretation:

S. apiospermum, S. boydii, S. aurantiacum and L. prolificans are common soil fungi, therefore a positive culture from a non-sterile specimen, such as sputum or skin, needs to be supported by direct microscopic evidence in order to be considered significant. A positive culture from a biopsy or aspirated material from a sterile site should be considered significant. Culture identification is the only reliable means of distinguishing these fungi from Aspergillus species.Serology:

As in cases of aspergillosis immunodiffusion tests have become valuable in the diagnosis of pseudallescheriasis. However, at present reagents are not commercially available and antigenic extracts have to be made in the laboratory.Identification:

Culture characteristics and microscopic morphology are important, especially conidial morphology, the arrangement of conidia on the conidiogenous cell and the morphology of the conidiogenous cell, in this case an annellide.Causative agents:

Scedosporium apiospermum, Scedosporiun aurantiacum, Scedosporium boydii, Lomentospora prolificans.Further reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Gilgado, F., J. Cano, J. Gene and J. Guarro. 2005. Molecular phylogeny of the Pseudallescheria boydii species complex: proposal of two new species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4930-4942.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co.

Warnock DW and MD Richardson. 1991. Fungal infection in the compromised patient. 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons. -

Zygomycosis (Mucormycosis)

The term zygomycosis describes in the broadest sense any infection due to a member of the Zygomycetes. These are primitive, fast growing, terrestrial, largely saprophytic fungi with a cosmopolitan distribution. To date, some 665 species have been described although infections in humans and animals are generally rare. Medically important genera causing systemic zygomycosis (Mucormycosis) Rhizopus, Lichtheimia, Rhizomucor, Mucor, Cunninghamella, Saksenaea, Apophysomyces, Cokeromyces and Mortierella.